Author: Geoff Currier

To preserve an 128-acre ecological gem, it took a man who loved planes more than money.

“When you see Katama from the air, the only thing that’s left of what Katama used to look like is this swath of open field where the airfield is — everywhere else is houses and pine trees.” –Mike Creato

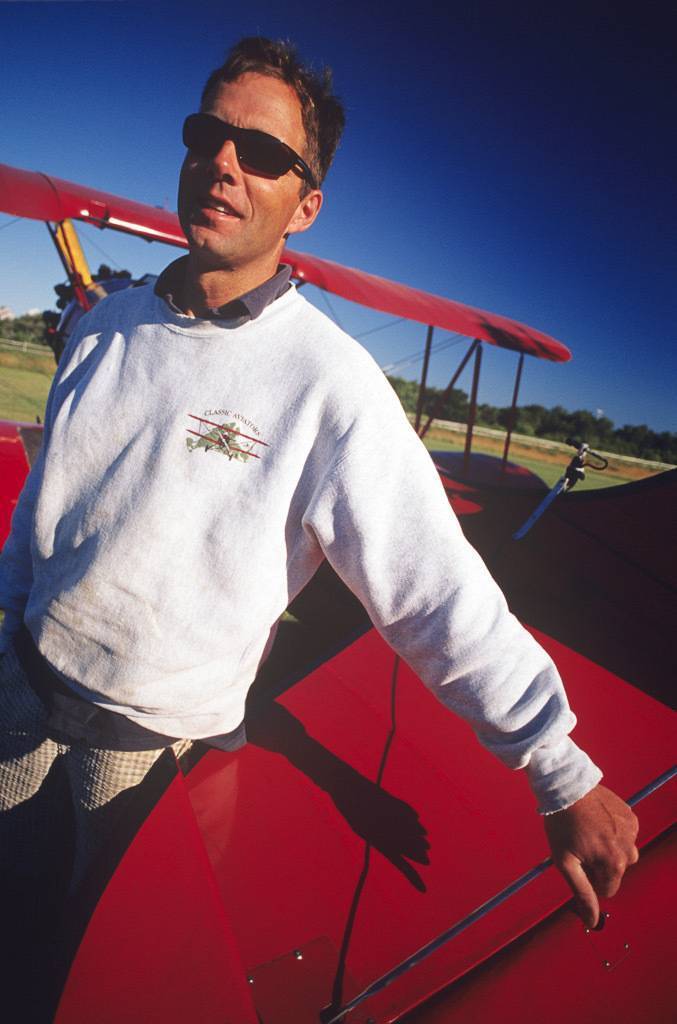

I caught Mike Creato on a good day. Good day for me, but not so good for Creato. That’s because Mike Creato co-owns Classic Aviators, which takes people up for biplane rides from Katama Airfield, and because the weather was looking iffy — fog was creeping in over the dunes of South Beach — he wouldn’t be giving any rides that day. And I would have a chance to talk to him about the Katama Airfield, which his family has had ties to for generations. I specifically wanted to know about how this little gem of an airfield, carved out of some of the most expensive and desirable real estate on the East Coast, hadn’t been snatched up by developers years ago.

We sat down at Creato’s desk in a wooden hanger that housed a 1940 Waco UPF-7 biplane. This fire-engine red aircraft sat staunchly on a cement floor behind Creato’s desk, surrounded by all forms of spare parts and paraphernalia, and hanging on a wall in back of the plane was a large rack of moose antlers and an old poster of Winston Churchill proclaiming “Victory.” I felt like Eddie Rickenbacker was about to walk into the hangar at any minute.

Creato told me the improbable story of how this little grass airfield by the sea came to exist in the first place. Today it’s the largest grass airfield in the country. Formerly pastureland, it was established in 1924 (making it one of the most enduring grass fields in the country), and used by the Curtiss-Wright Flying Service, one of the first flying schools in the nation, and later by the Martha’s Vineyard Flying Club, among others.

In a personal journal kept by Steve Gentle, Creato’s grandfather, Gentle wrote, “Many well-known aviators put their wheels down at Katama — Roscoe Turner, Howard Hughes, and Max Conrad — and there is some evidence that the Spirit of St. Louis was photographed at Katama.” In another entry Gentle wrote, “Many people still remember the air meet that was held in 1928, and was attended by around 10,000 people.”

Steve Gentle made his name as a masterful flight instructor, giving lessons to people at the airfield pretty much from day one. But when the stock market crashed, things got pretty quiet. Although Creato remembers his grandfather telling him that in the ’30s, a man came out from Florida every summer in a biplane and put on an airshow. “The way he got things started,” Creato said, “he would throw a chicken out of the airplane as he flew by, and whichever local kid caught the chicken, got a free ride — there were no rules back in those days.”

The airfield was closed during WWII; the Navy used it for target practice, and had a rocket range and a gunnery range there. Then in 1944, Steve Gentle bought the airfield — the day before the Hurricane of 1944, which left pieces of the hanger scattered all over the field.

Gentle wrote in his journal, “The corrugated sheet metal was strewn all over the area, with the hanger doors blown across Herring Creek Road and into the pines.”

With no hangar and no electricity, Gentle was nonetheless undaunted, and reconstructed the hangar. From then on, he and his family had a hand in running it continuously until 1985. The story of the airfield is interesting enough, in and of itself, but even more fascinating is the story of the land upon which the airfield rests.

The area around the airfield is known as the Katama Plains, a remnant of the Great Plains that once covered much of the Vineyard’s south shore.

Naturalist and MV Times “Wild Side” columnist Matt Pelikan wrote in an email, “Katama Air Park is one of the best examples of coastal sandplain grassland/heathland anywhere in the world. The airfield preserves populations of specialized plants and insects that are adapted to storm winds, salt spray, and periodic fire. Even by the Vineyard’s high standards, Katama is an ecological gem.”

Creato takes me through a little of the geological history of the plains. He explains that it’s basically a washout from the glaciers. “Sometimes I’ll get to fly around with a geologist,” Creato says, “and they’ll tell me stories about how the Island was formed.”

Apparently, when the glacier rolled across the Island, it stopped near the north shore, piling up boulders and debris almost a mile high. When the ice melted, there were no boulders left anywhere to the south, just sand; and that’s what contributed to the forming of the plains.

“What gets me even more,” Creato says, “is that this was all dry land after the glaciers melted and receded. There was no seawater between the Cape and the Vineyard until about 5,000 years ago, and the ocean was 30 miles off South Beach back then, out by the edge of where the continental shelf is.”

With the airfield back up and running after the war, and many aviators returning to the Island, Gentle felt he had found his true calling. He ran a charter business and gave flight instruction, and his wife Dorothy ran the snack bar. While no one was getting rich, at least Gentle was doing what he loved most in the world.

“My grandmother would say,” Creato recalled, “‘You have a year where you’re starting to get ahead, then one of the airplanes would need a new engine, and there would go your whole profit for the next two years.’ Then somewhere in the early ’60s my grandmother said, ‘You know, real estate is starting to take off; why not get a real estate license?’ They hung out a shingle, ran an ad in the paper, and after 30 days sold four houses, more money than they had made in the previous 10 years.”

With real estate giving Gentle a financial cushion, he stepped back from the airfield and leased out the operations to others. “People would come in and run it for a few years and see if they could make money,” Creato said. “Although I doubt many of them did.”

It was during this period that the airport came onto the radar for two special interest groups in particular — real estate developers and conservation groups. Conservation groups were interested in preserving the flora and fauna, and realized that their interests were aligned, ironically, with the people at the airfield. They were both interested in managing the property, and the conservation people appreciated that the airfield maintained the land.

“Katama Air Park is one of the best examples of coastal sandplain grassland/heathland anywhere in the world. The airfield preserves populations of specialized plants and insects that are adapted to storm winds, salt spray, and periodic fire. Even by the Vineyard’s high standards, Katama is an ecological gem” —Matt Pelikan.

Without the airport clearing and burning back the brush, the pastures would be carpeted in forests, much like it is today elsewhere on the Island. Creato says that he’s seen old aerial shots from the ’30s showing that from Squibnocket to Menensha, there was all pastureland, while today it’s mostly trees and houses.

In the ’70s Gentle made it known that he was interested in selling the airfield (to be run as an airfield), and he was approached by developers who were willing to pay him a fortune to buy the land. With quarter-acre zoning in Edgartown at the time, the 128-acre field could have potentially resulted in 120 units of housing. “My grandfather wouldn’t even entertain that idea for any amount of money,” Creato said, “because he would lose the airport and everything it stood for.”

Creato, just a young man at the time, suggested that rather than selling the airport, his grandfather could develop the 12 waterfront lots and sell them for three times more than he could get for the whole airport.

“Nope,” his grandfather insisted, “I’m not going to do it.”

Mike Creato pilots the red biplane for Classic Aviators. His grandfather, Steve Gentle, helped preserve the land. —Photo by Alison Shaw.

But in 1979, the town of Edgartown formed an alliance with the Nature Conservancy and the state that would prove to be the best of all possible worlds. In 1983, Edgartown, backed by a bond from the Nature Conservancy and a grant from the state, would offer to buy the airfield and operate it in the future. This would keep developers from potentially building 120 units of housing on the land. The town would hire a manager for the field, and lease it out to tenants in the future. And the Nature Conservancy would oversee the cutting and burning between the runways.

The town offered Gentle $1.5 million for the purchase of the 128-acre tract. The deal was somewhat complicated because Gentle had leased some parcels of land to several small farmers, and had to spend about $700,000 getting the property through land court. That left Gentle with around $800,000, a pittance compared to what he might have made had he sold it off to developers.

But as Mike Creato said, “It wasn’t all about the money; my grandfather added $800,000 to his retirement, so he knew he’d be OK, and he knew the airfield would live on in the future.” In 1986 the deal was finalized, and was the cause of much celebration. It was one of those deals where everyone — except the developers — seems to have come out ahead.

“When you see Katama from the air,” Creato said, “The only thing that’s left of what Katama used to look like is this swath of open field where the airfield is — everywhere else is houses and pine trees. I think everyone is pretty glad it’s here, environmentalists, aviators, and families who just love to sit outside and have breakfast at the diner and watch biplanes take off and land.”

And all because Steve Gentle liked airplanes more than money.

The crash of the P-15 Mustang

Hanging on the wall in a hangar at the Katama Airfield, up by the moose antlers, is a piece of a P-15 Mustang WWII fighter plane, “the best-looking piece of metal you’ve ever seen,” Mike Creato said. In June of 1975, the Oxford Warbird Club, a group of military airplane enthusiasts, decided to come to the Katama Airfield and put on an airshow — and they were bringing the iconic P-15 Mustang.

“Everyone who saw the plane was captivated,” Creato said, “The pilot was a WWII veteran, and flew it like he’d been flying it all his life.” The pilot took people up for rides all day Saturday, but at the end of the day he said he was tired and would come back the next day. Creato, who was just 14 at the time, asked his grandfather if he could get a ride when he came back.

But the next day, another pilot, John Crumish, was there to take the Saturday pilot’s place. “He was a good-looking guy in his thirties,” Creato said, “and he looked like what I thought a German fighter pilot might look like.”

Creato saw his grandfather talking to the new pilot and made eye contact with him, but his grandfather looked at Creato and shook his head ‘no.’

“I was ripped,” Creato said, “I thought he was being too conservative.”

His grandfather later explained that the new pilot was too new; he had only had about six hours flying the Mustang. And his grandfather proved to be right.

“Apparently the plane is not terribly hard to fly,” Creato said, “but there are about six things you just can’t do.” And not being fully familiar with the P-15, the pilot did something terribly wrong. He stalled while performing aerobatics, and he desperately tried to power out of the fall, but rudderless, the plane came hurtling down and crashed just feet from the administration building at the airfield. Crumlish was killed, but somehow no one else was injured, and no fire broke out.

It was a horrific day, but Creato learned an important life lesson — to never again question his grandfather’s judgment.

Recent Comments